If you’re a collector interested in late 19th century firearms, chances are you have (or should have) a rifle with this man’s initials (ESA) stamped into the receiver. Erskine S. Allin ran the Springfield Armory – not our present-day commercial manufacturer, but the federal armory based in Springfield, Massachusetts. Not only did Erskine oversee the federal government’s firearms manufacturing during the American Civil War at the Armory, but he was active in firearms design well into the Plains Indians Wars. He is probably most known for his innovative “trapdoor” design – the Allin Conversion – to convert the US stock of Civil War muzzleloaders into highly effective breechloaders. He’s a fascinating man during a very, very fascinating time in history.

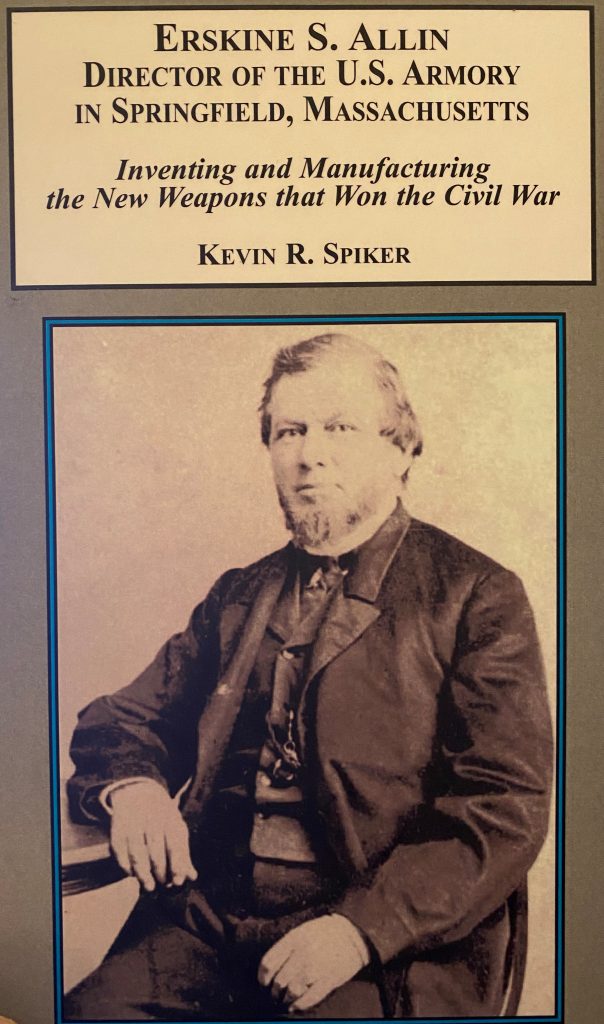

Now I’ve just received a book entitled, Erskine S. Allin, Director of the U.S. Armory in Springfield, Massachusetts: Inventing and Manufacturing the New Weapons that Won the Civil War. No kidding, that’s the title – like a callback to 18th or 19th century titles. The only thing missing is a sub-sub title like “In which it is revealed how awesome Mr. Allen’s contribution to firearms history really was.” Don’t get me wrong: I like the title and the book, and am excited to have it.

The book was written by Kevin R. Spiker, with an introduction by the well-known (in these circles) James B. Whisker, and published in 2014 by The Edwin Mellen Press. The Edwin Mellen Press has a “reputation” in academia for it’s relatively high price amongst other things, but I’m glad this book was published and that is to EMP’s credit. As Whisker’s introduction states, this book was “overdue”.

First Impressions of the Book Itself

Okay, first thing I’m going to say – because this annoys me to no end – is that the editing sucks. The editing is a disservice to the high quality of the authorship. It’s notable that nobody takes credit for the editing job on the copyright page. For example, on page 10 the following quote illustrates a pretty glaring but all too frequent mistake throughout the book: “It would be difficult to overestimate the influence that Erskine S. Allin on the armory system created by Congress in Nineteenth century America.” Missing words, repeated words, repeated sentences, missing characters.

I always miss typing words in drafts, but you’d think this and a few similar errors in chapter one would be caught by a basic rereading by someone who’s not the author. These periodic typos and grammatical errors are distracting, though you can guess how the correct sentence was supposed to be structured, assuming English is your first language. It’s very disappointing, as the level of effort that Dr. Spiker went to in compiling research and transforming it to a narrative is really good.

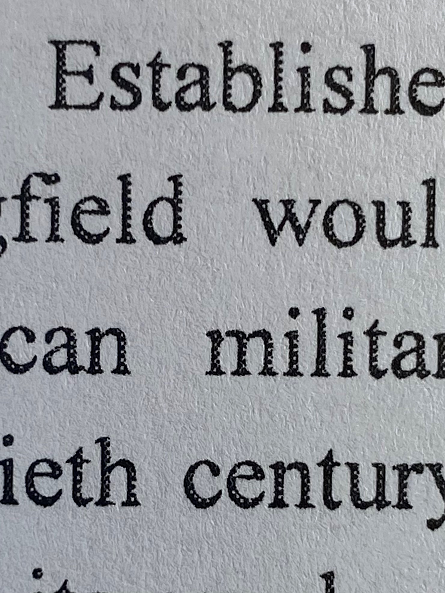

Also, the print quality is a little meh. The type is not very dark, but almost like a printer running low on black ink. If you look closely, as you can see in this close-up image of the text, you notice there’s a dithering that occurs on the print. At a normal reading distance from the text, this makes the black type appear more gray, or faded. If this was a $1.99 paperback from Barnes & Noble, like a royalty-free Don Quixote reprinting made in India, I’d be more understanding. But no! This is a hardcover book that cost over $170 direct from the publisher. Holy crap! At that rate, one expects a damn fine product.

The binding is good. I like the portrait on the front of the book – that of a younger Allin – as it makes him far more relatable/accessible, I think, than a picture of his older self.

What About the Content?

History books are full of rabbit holes and this one is no different. The author starts the book with a very high-level overview of the Armory and Allin’s life. One thing I like about Spiker’s writing is that he tells you when subsequent chapters will be exploring a topic in greater detail. Each chapter concludes with his endnotes, so you’ll find plenty of other interesting books and articles to look up at another time. That said, I wish the author was more liberal in his source references for declarative statements. Also, while I know footnotes can crowd a page, I prefer them to endnotes, which will force you to constantly flip back and forth between what you’re reading and the end of the chapter. That the pages have no heading to denote which chapter they belong to also makes finding the end-of-chapter a bit of a hunt.

I’m excited to read this book, despite my complaints about the quality of the compiled product. I doubt there will ever be a second edition, but I’ll volunteer to proofread it if the author is ever interested. I’m going to try and blog this book, at least a bit. There are all sorts of interesting facts, anecdotes, and history in here, not just about Allin, but the context in which his professional career matured. I’m looking forward to digging in and sharing some thoughts, as well as provide some links to explore some of the rabbit holes I find myself going down.

My suspicion is that this very valuable piece of scholarship will be increasingly hard to find over the years, and may show up on gun show tables if you’re lucky.