One finds a lot of interesting tidbits in the newspapers of yesteryear. For instance, on July 21st, 1871, the Springfield Republican notes that:

The war department has issued a general order, to-day, establishing the department of the Platte, with Gen. Ord as commander, with his headquarters in Omaha, Neb.

From Washington, The Springfield Daily Republican, Tuesday, November 21, 1871

I was recently combing through a list of US Army departments for my article on the Springfield Model 1881 Forager trying to determine how many Army “companies” existed in 1881. Seeing this headline about the creation of the Platte caught my eye.

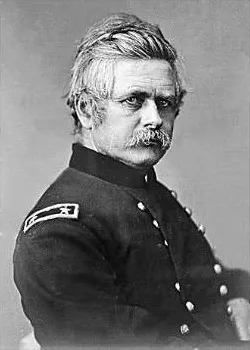

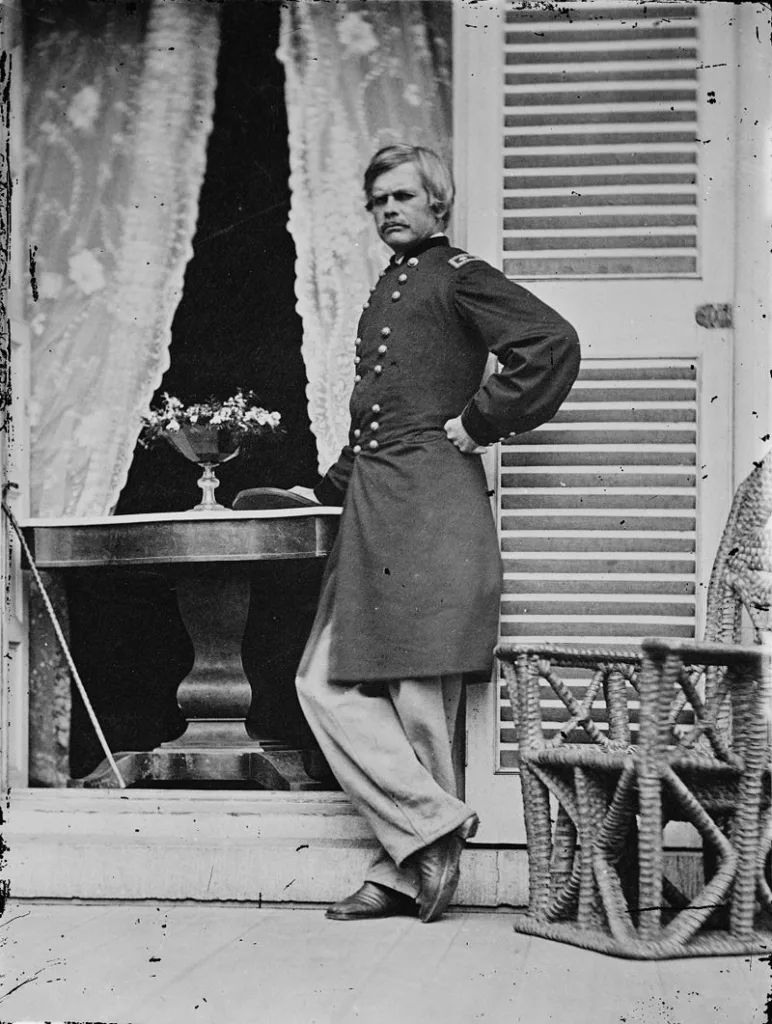

But who was this General Ord? Why, this would be Mr. Edward Ortho Cresap Ord, born in 1818, and passing at the age of 65 in in Havana, Cuba of yellow fever. Edward Ord was allegedly the illegitimate grandson of King George IV and Maria Fitzherbert! What?? We’ll come back to that.

Edward Ord’s early military career starts in the Second Seminole War, so let’s pick up there with some background because most of us don’t hear very much about the Seminole wars in Florida.

After the U.S. Revolutionary War ended with the Treaty of Paris in 1783 (back in the day, which was a Wednesday – literally, in this case), there was some dispute as to how much of the Florida territory Spain could lay claim to. Soon, accusations surfaced that Spain was harboring fugitive slaves and sheltering the indigenous population that was conducting raids on American territory. These were the Seminoles, a broad term that is thought to come from the Spanish word “cimmeron”, which meant “runaway”. The term was used to refer to all the various tribes/clans in the Florida region, whom the US ostensibly believed to be derived from the Creek tribe. An invasion of Florida, led by Andrew Jackson before he became President, happened in 1818.

This was the First Seminole War. The war ended with the United States purchasing Florida from Spain in 1821 after the initial annexation via invasion. Following this, we see a continued pattern that would keep going for many decades in the United States, where inbound settlers started to demand the forced removal of the Native Americans. The boundaries of a new reservation were established in central Florida, and in 1823, under the Treaty of Moultrie Creek, many of the Seminoles relocated to this area. But that was not the end of this tale.

Soon, there was a call to move the Indians West – entirely outside of Florida. A new region was identified in Oklahoma, thinking the Seminole tribes could go live with the Creek. A treaty was signed to affect this, but all the complications that would continue to plague such agreements well into the 19th century were present here – the chiefs signing the treaty didn’t have authority to commit on behalf of all the people it affected; charges of duress were leveled; etc. At this point, the United States sought to compel compliance with the treaty through diverse tactics but principally through limiting access to guns, a practice of economic sanction that had been used at this point for centuries against the indigenous populations.

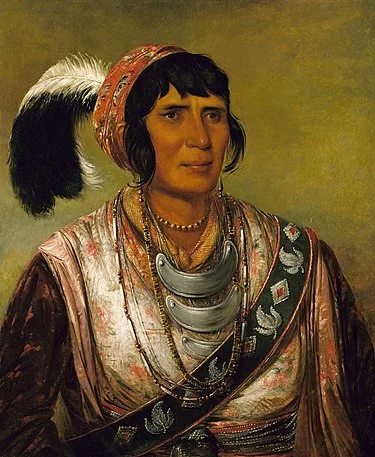

Well, understandably, people did not take kindly to gun control then any more than they do today. There was no “Gabby Giffords” of the Seminoles telling people to give up their guns. Quite the opposite: a chap named Osceola (pronounced Asi-yahola, according to Wikipedia) equated the gun control effort with the attempted enslavement of his people. He knew the score, saying, “The white man shall not make me black. I will make the white man red with blood; and then blacken him in the sun and rain”.

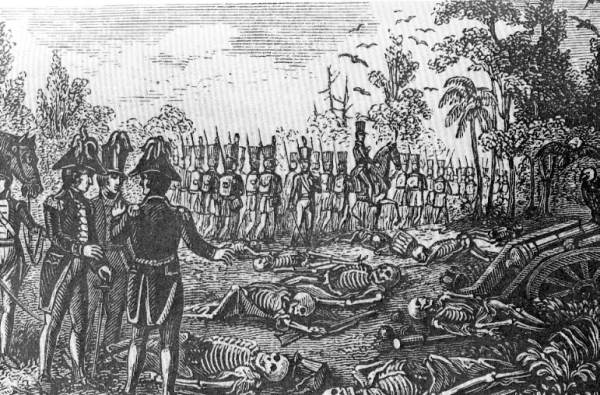

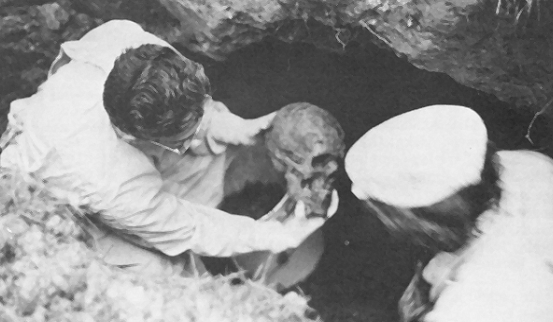

Things spiraled out of control at that point. The Dade Massacre in 1835, killing some 107 federal soldiers, left only three survivors. One of these was sought out and killed the next day. Another, Private Ransom Clark of Greigsville, New York, ultimately died of his wounds but leaves us the only written account of the ambush from a soldier that participated in it. It’s entitled, “The Surprising Adventures of Ransom Clark, Among the Indians in Florida”, and is worth reading in full. Here’s an excellent paper written by Frank Laumer of the University of South Florida in 1981 that reproduces it and provides some incredible context, background, and resolution of the events that day. He even exhumed Ransom’s body to investigate the claims of injury – we’ll come back to that as well.

Ransom Clark sure seems like a man who kept rolling a “20” in life, having survived two other close brushes with death before this event – the lone survivor of a capsized boat in the Gulf of Mexico, the survivor of earlier Seminole captivity. As was written in Beowulf, “Fate oft saves a man not doomed to die, whose courage fails him not.”

Clark recounts the opening onslaught:

It was eight o’clock. Suddenly I heard a rifle shot in the direction of the advanced guard, and this was immediately followed by a musket shot from that quarter. I had not time to think of the meaning of these shots, before a volley, as if from a thousand rifles, was poured in upon us from the front, and all along our left flank. . . . We were surrounded by about 900 Indians and 100 Negroes who had run away from their masters’ plantations and joined themselves to the savages. With demoniac yells and shouts, they commenced a brisk and galling fire upon us.

Ransom Clark, The Surprising Adventures of Ransom Clark Among the Indians in Florida, 1839

And if you’re wondering, yes, Virginia, “demoniac” is a legitimate spelling of what we commonly see printed “demonic”, coming from the Old French, “demoniaque”.

Clark recounts that the opening volley seemed to cut down at least half their number. The subsequent losing defense which he details brings to mind something from the Teutoburg Forest, but in this case the site of the ambush was never lost. Soldiers were dispatched to recover the site. Laumer has collected a number of accounts in the paper mentioned above, but he quotes two officers at the scene. The first details their approach to the scene.

[F]irst indications of our proximity were soldiers’ shoes and clothing, soon after a skeleton, then another, then another! [S]oon we came upon the scene in all its horrors. Gracious God what a sight. . . .

Lt. James Duncan, quoted by Laumer, Frank (1981) “The Incredible Adventures of Ransom Clark,” Tampa Bay History: Vol. 3 : Iss. 2, Article 3.

Next, Laumer quotes Captain George A. McCall, who wrote in his book, Letters from The Frontier:

I carefully examined our poor dear fellows, both officers and men, as they lay within the little fort, in posture either kneeling or extended on their breasts, the head in very many instances lying upon the upper log of their breastwork; and I invariably found the bulletmark in the forehead or the front of the neck. The picture of those brave men lying thus in their ‘sky blue’ clothing, which had scarcely faded, was such as can never be effaced from my memory.

Cpt. George McCall, quoted by Laumer, Frank (1981) “The Incredible Adventures of Ransom Clark,” Tampa Bay History: Vol. 3 : Iss. 2, Article 3.

The illustration to the left paints (cuts?) a macabre scene, the lone 6lb cannon still in its carriage amongst the dead. In reality, the skeletons were still clothed, and I think the cannon carriage was destroyed.

Ransom Clark reportedly suffered no less than five gunshot wounds, and I believe it was four ball and one of buckshot to the chest. Laumer’s paper approaches Clark’s writing with skepticism, but after much research Laumer basically confirms that his account is on point. Laumer examined many other contemporaneous accounts, including newspaper articles, journals from those attending to Clark after he returned to the fort, and even exhumed Clark’s body to verify the injuries. It seems the amazing details of his story are largely true. Again, I can’t recommend reading Laumer’s paper enough. Laumer went on to write a book, entitled Dade’s Last Command, which I’m now reading.

Fate oft saves a man not doomed to die, whose courage fails him not.

Beowulf

While this massacre was taking place, Osceola and several others shot and killed seven soldiers outside Ft. King. Andrew Jackson was now president, and these incidents and a few more put the United States in a severely vengeful mood and precipitated the Second Seminole War, this time with a focus on the Seminole themselves rather than Spain. It was in this war that a young Lieutenant Edward Ord would serve.

Private Ransom Clark, Company C, Second Regiment Artillery, would end up dying five years after the Dade Massacre, in November of 1840, from the wounds he sustained which would never heal. Just a year earlier, in 1839, Edward Ord graduated from West Point and was commissioned as a second lieutenant in Third Regiment Artillery, sent to Florida, and served in the Second Seminole War which carried on for another two years.

Surveying California

After the conclusion of the war, the now First Lt. Ord served at stations on the East Coast but finally in 1846 he was sent to California as the Mexican War broke out. Ord traveled around South America by ship accompanied by none other than a young Lieutenant William T. Sherman. These two, who had been roommates at West Point, arrived in California too late to take part in the war. As the California gold rush took off, they both took side work in 1848 surveying the townsite of Sacramento, Pueblo de Los Angelas, and some private gold claims. Pueblo de Los Angelas? Yes, the future metropolis. Ord, as compensation for this survey work, was offered 160 acres of land in what is now the downtown LA business district but opted for a cash payment of $3000 (about $100,000 in 2023). This preference for cold hard cash will come up again in the mysterious story of royal lineage.

Oregon Fights of the Rogue River

After his survey work was done, Ord oversaw the Third Regiment Artillery at Fort Benicia in California around 1855. Not much was happening in California that required the services of artillery at the time. In 1856, Ord would find himself in Oregon fighting the Chetco, Shasta Costa, and the Macanootenay tribes in the Rogue River region of Oregon. Serving under an inexperienced Colonel Buchannan, we see Ord’s experience from the Seminole War pay out in correcting several tactical mistakes of his superior officer. In his diary on March 22nd, he states:

The men and the women disgusted with the Col.’s arbitrary decision & positive manners, which by the way is quite enough to disgust them. He is not the man for the people or the emergency.

Ord, Edward. Diary of Edward Ord. March 22nd, 1856.

Ord found notable success in his engagements and may be credited to some degree of turning the fortunes of the settlers in the region. In his diary on March 23rd, he records an engagement that won him praise. I reproduce this entry verbatim, as it is written in his diary, including spelling mistakes and shorthand, but have augmented names with some notes in brackets.

Started at 8 A.M. 112 men [Infantry Captain Delancy Floyd] Jones & my comps Lt. [John] Drysdale & Dr. C. A. Hillman with us. He is good fellow. Had an awfully hard march 11 miles to Mikonotunne village on pretty river bottom backed by timbered hills in front the rapid river on one flank willows on other spur of the mountain with timber on it. We burned the houses 13 in no. & then the Indians attacked us from timber in rear & on rt. flank but I had the men ready and whipped them from one ridge of timber to another & finally across the river. We then slowly left in good order, but the rascals dogged us & wounded Sgt. Nash of rear guard, badly we . . . tired men made litter but it wouldn’t work I then took him before me & carried him till trail was visible then made another after trying to pack him on a mule but he fell off & carried him to camp on ridge near Cantwell’s prairie. This march through the dark woods, without visible trail, with men so exhausted as to be hardly able to get along, for they had not eaten or drank for 6 or 8 hours, was one of the hardest I ever endured * * * however at the battle of the day before we killed 8 Indians, besides squaws and wounded at least as many more, and I am told it is the first time these Indians have ever been driven from their position, on this river.

Ord, Edward. Diary of Edward Ord. March 22nd, 1856.

Bernarr Cresap, in an article for the Oregon Historical Quarterly, provides the following review of the action:

Indeed, Ord had shown considerable skill and daring in the Macanootenay fight; his direciton of the affair was admirable. The effect of the action was to raise his prestige considerably in the army as well as among the people of the Pacific Coast. But the importance of the fight was more than personal.

Cresap, Bernarr. “Captain Edward O. C. Ord in the Rogue River Indian War.” Oregon Historical Quarterly 54, no. 2 (1953): 83–90. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20612097.

He goes on to quote the San Francisco Daily Herald as saying:

This is regarded by the people of Rogue River as the first regular defeat of the Indians since the beginning of the war. It is the first time the whites have charged the Indians after having been attacked by them . . . . This, with a little more powder and ball is expected to bring them to terms . . . .

San Francisco Daily Herald, April 18, 1856.

If you’re interested in finding the whole article, it was reprinted in the Triweekly Washington Sentinel on May 20th, 1856. Captain Ord is given credit for the action.

War is such a sorrowful business, and the Indian Wars spanning the 19th century are especially difficult to read about. Captain Ord was fighting on the West Coast before the Civil War had ever started, and a good ten years before some of the more famous battles of the Plains Indian Wars took place. Pacifying the rebellious tribes in Oregon was not easy business for the Army. The Indians, while increasingly destitute fought with determination and it’s no secret that their attacks could be as ruthless as those of the Army. It clearly began to affect Ord. In June, we see him make the following entry in his diary (emphasis mine):

This P.M. news from Bledsoe and Augur, had each attacked Indians, camped at the marked rock 12 or 15 miles below. First had killed 7 and 2nd 8 Indians, had captured 4 canoes and a dozen women & children. The men behaved well & took Inds. by surprise I am glad Bledsoe had done so well 2 of his men were shot by some of Augur’s party from opposite side by mistake the Col. is quite elated, and thinks we will all soon be able to go in. Separate dispatch came from Augur & Bledsoe. I am glad I didn’t go down for I should have attacked before daylight and many women & children would have been killed, for twice the treacherous attack on Capt. Smith’s command ’tis difficult to show any quarter, the men are disposed to kill all.

Ord, Edward. Diary of Edward Ord. June 6th, 1856.

Woof. I leave it to you to read about the dramatic events happening in the region at the time, but it will suffice to say for my purposes that it was bloody and all around sorrowful for all involved and represented a continuation of the dynamic seen between settlers and indigenous populations.

This chapter of the Indian Wars was drawing to a close as the tribes began to turn in guns and relent to the overwhelming weight of their invaders. Ord’s duties were now turning to facilitating the surrender of those still living in the wilderness and he witnessed their devastation as hundreds of them marched over the landscape.

Sunday, June 8th: At 2 P.M. a lot of Inds., 4 men 9 squaws and some children came limping and crying (these squaws) into camp. A girl 12 years was drowned coming down the river, poor devils. The decrepit and half-blind old women are a melancholy sight to see. To think of collecting such people for a long journey through an unknown land, no wonder the men fight so desperately to remain after they have driven all the white settlers too out of it. It almost makes me shed tears to listen to them wailing as they totter along. One old woman bringing up the rear, her nakedness barely covered with a few tatters and barely able to walk. They had been a long time getting here and many of them have lost all they had by the capsizing of the canoe. some others were near drowning. The girl was on the back of a man who was swimming ashore with her. He had a boy, too. The girl was washed off, canoe smashed as it went over the rapids.

Tuesday, June 10. Leave camp Big Bend A.M. I in rear. [Volunteers] going down . . . . We marched down river 2 miles & turned up a steep hill, at mouth of creek rather tough on the old squaws, one old fellow & his wife already behind. Poor old woman begins to fall down before we begin to climb the mountain & she broke down entirely short distance up. 1 mule rolled down over hundred yards. Old man “Limpy” went and got a horse. Old squaw fell off. I then took her in front of me, pretty hard to stand it. We were tired when got to camp top of hill, and I was quite sick on the road. Gave up my mule to lame girl and broken down old squaw, girl quite childishly happy. First time maybe in her life she has had so much kindness shown her

Ord was very clear-eyed about the contradictions in these wars, the mad loss felt by all those involved. He wrote a letter to the New York Herald in February of 1856 trying to educate those on the East Coast about the realities of West. It’s lengthy, so I won’t reproduce it here, but the Library of Congress has an image of the paper for your reading pleasure. E.O.C.O’s contribution starts at the top of the fourth column from left.

The Civil War

Investors may debate Ord’s wisdom of taking the Los Angelas cash instead of the real estate, but Ord was a rather shrewd gentleman and did know a good thing when he saw it. At the end of the Civil War, he was present at the McLean house surrender, and bought the marble-topped table that General Robert E. Lee had sat at for $40 (about $730 in 2023).

And speaking of the Civil War, Edward Ord was in the middle not only of the surrender meeting, but the circumstances preceding the surrender more broadly. He had floated the idea of peace talks between Grant and Lee via an adjunct to Lee, and while these ultimately came to naught, the “Army of the James” which Ord had commanded would prove instrumental to forcing Lee to the marble-topped table at the McLean house on April 9th, 1865.

The Assassination of President Lincoln

Five days later, on April 14th, 1865, President Abraham Lincoln would be assassinated by James Booth at Ford’s Theater. General Grant’s immediate suspicion was that the erstwhile Confederate government was behind the killing – he was prepared to rain down hell on the Southern states in retaliation. Grant appointed Ord to investigate the assassination and prove or disprove a link to the Confederacy. Ord’s investigation would determine that Booth was effectively a lone wolf, and that the Confederate government did not have a hand in the killing.

And speaking of conspiracy theories, Grant himself was suspected of having a role in the assassination. He and his wife Julia were supposed to accompany the Lincolns to the theater that night but bowed out at the last minute. Did Grant know something rotten was afoot? Turns out we find Ord in the middle of these circumstances too!

Supposedly, Ord’s wife, Mary, had the audacity to ride her horse next to President Lincoln’s horse while Lincoln was out visiting the Army officers. This sent the chronically jealous Mary Todd Lincoln into a rage. Grant’s wife, Julia, spoke up in Mary Ord’s defense, and Mary Todd turned her wrath upon Julia. This was not the first ill-treatment of Julia by Mary Todd Lincoln and Julia took it very badly this time. When Mary Todd invited them to the Ford Theater as guests, they refused. General Grant and his wife Julia would have been joining the Lincoln’s at the theater the night of the assassination were it not for that kerfuffle with Edward Ord’s wife. Had Grant been at the theater that night, one can imagine several alternate outcomes to Booth’s deadly endeavor. You can read more about Mary Todd’s jealous nature at this New York Post article.

No Rest for the Weary

Ord was put in charge of the Fourth Military District after the Civil War and oversaw reconstruction efforts for a time. From 1868 to 1871 he returns to the Department of California, this time in charge of it. We’ve now essentially caught up to the Department of the Platte, which started this article in late 1871. In 1872, he participates in a buffalo hunting expedition to host the visiting Grand Duke Alexei Alexandrovich of Russia. None other than Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer accompanied them on this trip.

I have pointed out in other articles how the American East did not even consider that they had an ongoing war out West once the “War of the Rebellion” had concluded. Their fears and interests largely focused on the wars in Europe. You can see this reflected in the major newspaper real estate – how much is dedicated to the acts of Napoleon and the Prussians, and it seems only occasional anecdotes about the “Indian Affairs” showing up in the Eastern papers. Up until the disaster that was General Custer’s foray into a Sioux encampment in 1876, the policy of the federal government towards the mess out West had arguably been lackluster, unfocused, and merely “managed”. The Army was underfunded for the task, and even by 1880 you’d still find the Army complain about their policing role stuck between settlers and the indigenous population.

However, the people out West, indigenous and settlers alike, were living in violent conflict every day. To them, it seemed like a very real war. Tribe against tribe, settlers against tribe, more real than any conflict in Europe.

Salt Lake, Aug. 17 [1872] – The Indians of San Pete are still committing outrages . . . There is no doubt the Indians are fairly on the war path, they having bravely declared their intention to fight . . . J. D. Page, telegraph operator at Mount Pleasant, was attacked last night by Indians when leaving his office and was terribly wounded in the head by tomahawks. The wounds are supposed to be fatal.

New England Farmer. August 24, 1872

North Platte, Neb., August 11 [1873] – One hundred Pawnees, mostly women and children, slain – shocking mutilation of the bodies by the murderous Sioux . . . After a successful hunt, in which [Pawnee hunters] had killed nearly one thousand buffalo, and being heavily laden with meat and hides, on their return home they were surprised in camp by Sioux, supposed to be one thousand strong, and before they could escape or make successful resistance, nearly one hundred men, women and children were slain. The wounded, dead and dying women and helpless children were thrown into a heap and burned in the most barbarous manner possible. . . Much excitement prevails and the spirit of war is running at fever heat.

Account of Capt. Anson Mills, via telegraph on Aug. 11, 1872. The Herald and Torch Light. September 3, 1873.

At this point we find General Ord in a largely administrative role in Omaha. He gives interviews to the newspapers about condition and prospects of the territory he overseas and struggles to respond to one crisis after another as best he can and with the resources available.

By 1874, a fed-up newspaper in Nebraska calls out what it sees as the silliness of imagining that the conflicts are best handled by the “peace” department rather than the “war” department. After an Indian Agent, Appleton, was killed, they wrote:

The events of the past few days have demonstrated anew the absurdity of keeping the Indian affairs in a separate department from the military . . . There is too, what might be expected from two rival departments, jealousy instead of cooperation. The beauty of this is seen in the action of Saville, the agent, in his present trouble. Instead of applying to General Smith, the commanding officer at the nearest military post, he ignored the military entirely and reported to the Secretary of the Interior [whose] functionary made known the state of affairs to the Secretary of War, who in turn informs General Sherman, who telegraphed to General Sheridan at Chicago, who ordered General Ord at Omaha to instruct General Smith at Fort Laramie to do all in his power to help the agents at Red Cloud and White Stone agency. That General Smith has always been ready to do. In the mean time the dead body of Appleton is a silent but effective protest against a further continuance of such expensive foolishness.

A Humiliating Spectacle. The Nebraska State Journal. February 20, 1874.

This same paper would say that Nebraska was losing a “friend” in Ord when he transferred out. To boot, there’s a town in Nebraska named in honor of Ord still there to this day.

In 1875, Ord was succeeded in the Platte by General George Crook. Ord now took over command of the Department of Texas until 1880 when he retired.

“Fogeys at Forty”

Ord had already been thinking about retirement while serving in Oregon, as his diary makes clear. In fact, between his complaints about the idiocy of Colonel Buchannan and the rough responsibilities he held while serving on the Rogue River, you can understand the weariness expressed in his New York Herald article in ’56:

We wear out in Uncle Samuel’s army faster than they do in the navy, as we have no house over us where we go. Most of us are fogeys at forty; exposure in climates from Panama to Puget Sound tells on us. In my regiment, for ten years, two first lieutenants out of twenty (hardy fellows) died or were killed yearly. So we who live get to be majors at forty-five or fifty, but we are then old bundles of worn-out bones and muscles.

Ord, Edward. Our Correspondent in Vancouver, New York Herald. February 17, 1856.

To think that this man was only approaching the horizon of the U.S. Civil War, and further adventures out West is exhausting.

After retiring, Ord eventually moves to Mexico, hired by the Mexican Southern Railroad. While working there, he contracted yellow fever. He travelled back to New York, and then to Havana, where he succumbed to the illness in 1883.

Names and Rumors of Royalty

Edward’s middle name, Ortho, by the way, is Greek for “straight, upright”, and we often see the word today as a prefix for words like “orthogonal”, which one might use to describe my earlier digression into the story of Ransom Clark and the Second Seminole War.

With a name like Ortho, is it any wonder that Edward Ord would become a surveyor and be considered a math whiz? Edward’s second middle name, Cresap, was a surname from his mother’s side of the family.

So what was up with the connection to royalty? Ord’s father, James, who died in 1873, was the supposed illegitimate son of King George IV and the Catholic Mary Fitzherbert. This marriage was considered illegitimate because George’s father (George III) had not consented to the union. Dare we say he was “mad” about it? Furthermore, Catholics were not allowed in the royal line of succession. There are strong historical implications that Mary did have children by George, including people observing that she looked pregnant at times. She also refused to sign a declaration that she did not have children by George. There’s an interesting article in the Daily Mail about the descendent of James Ord living in Utah in 2016 and his pursuit to uncover the mystery of his royal lineage. I’ll not rewrite the information here, but James Ord seemed to have some very wealthy and unexplained benefactors as he grew up in the United States. The article goes on to say,

As late as 1944, another of [Fitzherbert’s] titled descendants, the Honourable Lady Beatrice Chichele-Plowden, claimed that both Queen Victoria and her son Edward VII blocked moves to unseal the papers. Lady Beatrice made another sensational claim: James Ord’s family in the U.S. had sent her a copy of a letter from William IV, George IV’s brother and successor, offering him the title of Duke of Malta or a cash payment. Ord, she claimed, had chosen the money.

Leonard, Tom. “Could this ex-Mormon lawyer be the true heir to the British throne? A scandalous royal marriage, George IV’s love child and a very intriguing question”. Daily Mail, June 27, 2016.

Well. If true, apparently the penchant for cash payments may have been congenital if not congenial. I’ve never seen a follow-up to this, or news that genetic testing was ever allowed to validate the ancestry of the modern-day James Ord.

Edward Ord was a military man through-and-through. He witnessed an amazing breadth of history and often was in the midst of its messy formulation. Quite the life!