Now for something different. I’ve been posting quite a bit on the Trials of 1870-73, including a list of rifles examined by the first review board under Schofield. There’s far more I intend to post on this topic because it’s really where my research energy is focused right now. It’s good to take a break though, so this is something completely unrelated to the 1870 rifle trials.

Let’s step back in time to the Civil War era and take a look at a really cool “mystery carbine”, made on the East Coast, destined for the Mississippi River, and ending up in Apacheria after the war. I had a conversation with some folks on CivilWarTalk.com about this, and posted a fair bit of reference material about it, so I’ll consolidate it here and add a little more color.

Let’s have some fun with this article and imagine we saw this gun on a table and have to identify it ourselves. Here she is:

In the photo above you can see the firearm in question. Let’s look at what we have using some detailed observation.

This is clearly a Sharps firearm, based on the characteristic receiver. We can identify it as a carbine, not a rifle or musket, based on the short barrel length. To get perspective when glancing at a gun, compare the length of the barrel to the length of the stock. Obviously a carbine barrel will be closer in size to the stock while a rifle barrel will be obscenely longer. While the short forearm grip is also a good first glance indicator that it’s a carbine, it’s certainly not a consistently reliable characteristic exclusive to carbines. We can see that this is a straight-breech Sharps, as opposed to the earlier slant-breech models (more on that later). This particular gun has no patchbox in the stock, which became a standard pattern after 1863 but was somewhat more rare to be missing them prior to this date. As well, this model does not have a brass band around the foregrip and barrel, but is fitted with iron furniture, including the buttplate. We can also take note that in the profile of the receiver, particularly behind the hammer, we can see the stepped pellet primer system patented by Richard S. Lawrence.

Most Sharps carbines were made for cavalry use. So one thing that jumps out is the presence of a rear sling swivel. The U.S. Navy did not order Sharps carbines with a rear sling swivel, and it wasn’t until 1859 – to my knowledge – that the Army started requesting them on their Sharps orders. Flipping the gun over, we see another glaring contradiction with a typical cavalry carbine set up. There’s no ring and bar set! How can it be a saddle-ring carbine without a saddle ring? What’s more, there’s no inlay for the plate with which the saddle ring bar would have been secured to the stock, nor is there a hole above the rear lock plate screw where the bar would be secured to the metal receiver.

The following photo is a different gun, but a typical example of a Sharps carbine made for cavalry use, showing what the left side of the wrist would look like:

So you can see that our gun isn’t simply a carbine with the saddle ring and bar removed, otherwise the stock would show the shallow channel where this piece would have been inlaid. There would also be a hole in the receiver where the bar used to be affixed. No, this is something different.

Identifying the correct model of any rifle, let alone the generation within the same model, can be challenging. Older guns are often confused for something they’re not because of the dates stamped on the receivers and barrels. These can include patent dates, manufacture dates, or model numbers. For instance, a model 1868 trapdoor Springfield often gets confused as an 1870 because most examples, counterintuitively, have the year 1870 stamped on them. There’s also the cliché of someone thinking their Winchester “Model 1894” was made in 1894. Point being, be cautious with stamped dates, and pay attention to other details. I like the idea of identifying a gun by profile like a submariner would learn ship silhouettes in the early 20th century.

Knowing the visual details of the gun helps to quickly identify what you’re looking at, versus having to read sketchy imprints. This is particularly helpful when quickly scanning photos at an online auction site. Regardless of what the seller says it is, buyer beware.

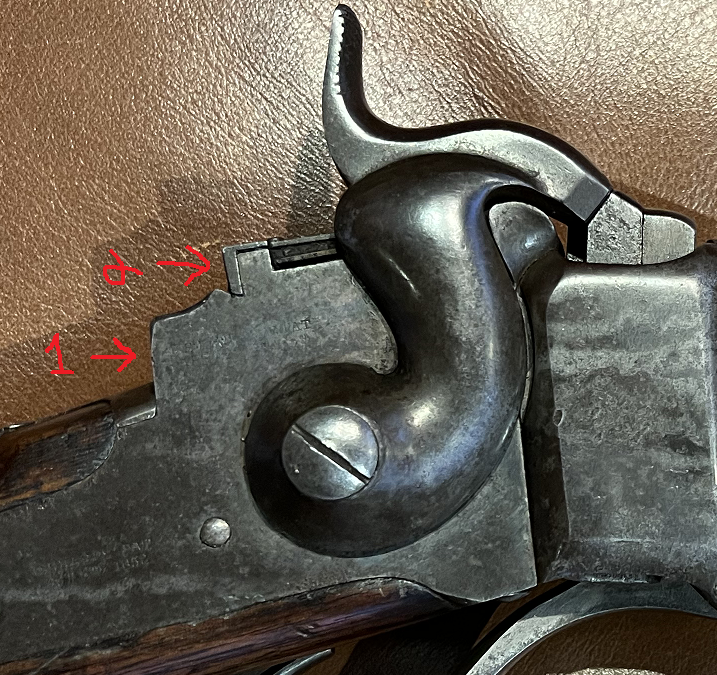

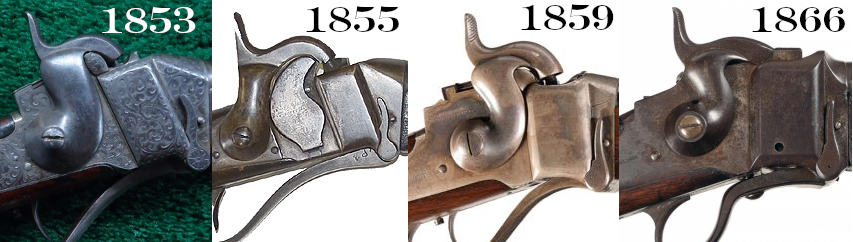

Remember how I mentioned the primer system we see just behind the hammer? Notice how, in the first photo, it has two stepped tiers on it? This is a quick tell that the rifle is no earlier than a model 1859. The preceding model, the 1855, had nothing resembling this. The model preceding that one, the Model 1853, did have a tape primer system behind the hammer, but is only one tier, no second step like the later guns have. I’ll illustrate these in a comparative photo in a bit.

I mentioned straight vs. slant-breech guns – that block you see ahead of the hammer that stands proud of the receiver was tilted backwards with a dramatic 112 degree angle on the slant-breech guns. The 1859 was the first model to move it back to its original perpendicular orientation relative to the barrel. So we know the gun is no older than an 1859.

All of the original Model 1859s had brass furniture. Since we have iron furniture, we know it’s no earlier than a “New Model 1859”.

This is all pretty confusing so here’s an image to illustrate what I’m talking about with the receiver profiles.

See how 1853 and 1855 have the “slant-breech” as opposed the straight breech? Also see how the priming systems change the profile from 1853-1859, and then just disappear on the 1866?

So now that we’ve established a lower boundary to the age, how new is it? The first rifle to really have an obviously different profile from the Model 1859 is the Model 1866, as shown above. In between the Model 1859 and the Model 1866 were the models 1863 and 1865, and they are virtually unchanged in profile from the 1859. None of the 1863s had patch boxes in the stock. There are some internal changes but nothing mechanical changed that would be evident from a quick glance on the 1863. The 1865 was not really a different model at all – just a rebranded 1863.

After the Model 1866, which was a metallic cartridge firearm, later models like the Model 1867 and Model 1868 started to revert to a similar receiver profile as the 1859. Why? Because the Model 1867 & 1868 were conversions of 59’s, 63’s, and 65’s to cartridge firearms. They literally are older guns, just with relined barrels and with receivers modified for metallic cartridges.

It must be at least a New Model 1859 or 1863, or a conversion of the same (Model 1867/68). The ’59 and ’63 are hard to tell apart in profile, but there are internal differences that would disclose the model. Whether it’s a conversion or not is pretty obvious by looking under the hammer. An unconverted New Model 1859 will have a nipple/cone under the hammer to hold a percussion cap. On a converted New Model 1859 (now most likely a Model 1868 pattern conversion), the nipple will have been replaced with an anvil for the firing pin. The hammer also has a slightly different contour.

Now, as it happens, the New Model 1859 and New Model 1863 have these designations stamped on their barrels. Why didn’t we just start there? Well, the other details of the gun matter in identification, not only to quickly identify what you may be looking at, but also to avoid franken-guns, cobbled together out of parts from different models and represented as something they’re not.

Let’s note another visual clue on the stock – my first photo in this article doesn’t do it great justice but on the left side of the wrist of the stock, just below the tang of the rifle, you can see a cartouche typical of U.S. military inspection. We now know we have an American military gun. If it was military it was either for the Navy or the Army. If it was for the Army, it would typically have a ring and bar for cavalry use. If it was Navy, it would have had brass furniture to help against salt air corrosion (the barrel band and butt-plate) and no rear sling swivel. Our gun fails both these tests.

So what is it?? Turns out that this variant of the Sharps New Model 1859 Carbine was a mystery for many years, even relatively soon after the war – the “rest of the story” was only recently solved through some diligent research work published as recently as 2019. Part II will explain everything.